An Overview of the Incident

Command System (ICS) in Common English

Updated March 10, 2025

If you have ever glanced over, reviewed, or tried to read any ICS training literature (named with the more simple "IS") and felt dumbfounded by what you encountered, be not discouraged. I felt the same way, and I have a master's degree in public affairs. Although my degree did not land me behind a soul-sucking desk in a bureaucracy, I did learn officialese well enough to be able to translate the language into common English.

It is important to know going in that FEMA's basic ICS training has the appearance of a stress test intended to separate those comfortable with uncertainty and confusion from those who would be happier in a more structured profession. Whether this stress-test style is intentional or not is open to debate. In any case, we will start as simply as possible.

What is a System?

First, realize that system is a fuzzy concept. Our working definition will be: integrated components that form a functioning whole. In all fairness to the authors of the ICS literature, a system can be extremely complex because it could be composed of lesser systems, semi-systems, and individual parts, items which we will collectively call components. A system itself can be a component of a larger system.

Likewise, know that the boundaries between components can be fuzzy. For example: Is a USB flash drive a component of your computer system when it is in your pocket? This could be argued both ways, but all it comes down to the fact that system is an abstract concept that humans have created to help us understand our world. Nature does not distinguish your respiratory system from your muscular system; without one the other would not exist.

Secondly, realize that a system and/or its components can be either tangible, intangible, or a combination of the two. Keyboards can be touched and held. Software has no physical presence in the world, but—like our souls—still exists. Both keyboards and software are components of computer systems.

Thirdly, realize that with enough mental gymnastics, almost anything can be called a system. For example, a self-adhesive bandage could be called a system to protect a wound. A bottle could be called a system for carrying water. A rock and a driveway could be called a system for compressing an aluminum can.

Fourthly, realize that if you overthink the concept, you will shorty arrive at the conclusion that everything is an integrated component in the great system that we call the Universe. For example, a computer system linked to other computer systems are components of the Internet system which is powered by multiple electrical systems which have wires and screws as parts, which are created by manufacturing systems, which are managed by social systems, and so forth.

Fifthly, realize that there are no standard names for system components. Thus, you will see systems described in terms of areas, agencies, divisions, departments, parts, pieces, processes, policies, principles, structures, sections, elements, groups, teams, or any number of other names. If you get confused over names, it is not your fault.

Sixthly, realize that some systems can self-mutate, which means they can grow, shrink, or change according to a situation. For example, a system for selling candy dispensers over the internet could change into a global auction system for selling diverse items.

Finally, know that ICS is fundamentally a management structure. For an EMR or EMT, the critical points to internalize are who your manager is and how to protect yourself from causing or getting into trouble. However, if you want to advance professionally (become a highly-paid bureaucrat, for example), a greater mastery of ICS is required. This should not be difficult to achieve after gaining some experience.

The Painful Birth of ICS

Imagine trying to extinguish a large forest fire with all the firefighters doing whatever they decide for themselves is best. It is not difficult to picture a horrific scene from some type of a nightmarish clown convention.

Following a poor response to its 1970 fire season, California started to develop its FIRESCOPE resource coordination system. FIRESCOPE, is an acronym for Firefighting Resources of Southern California Organized for Potential Emergencies. ICS has its history in FIRESCOPE, LFO (Large Fire Organization, an earlier wildland fire management system), and World War II military command and control systems. FIRESCOPE still exists. The 911 Massacre further shaped ICS, notably in its position relative to the larger system.

(The links in this article are not necessary to understand this article but are included in case you just can not get enough of ICS. Nevertheless, you should plan on reading this at least twice in order to pull together the graphics and text. Also I am trying to match my capitalization with the ICS literature in case anyone is wondering.)

The Basic Structure of ICS

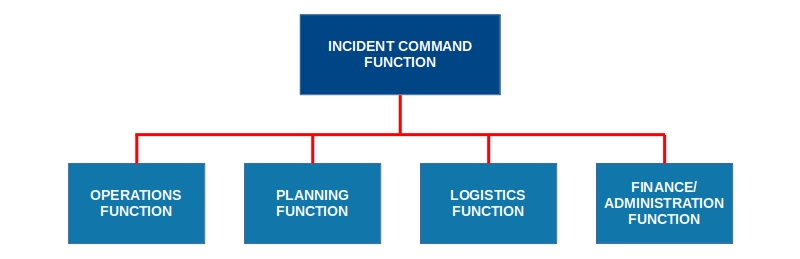

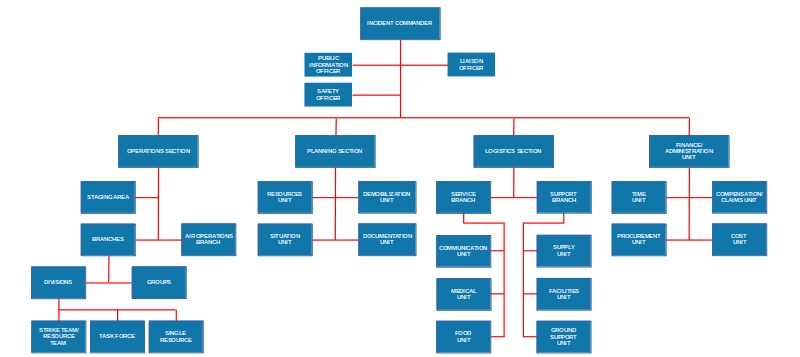

ICS has five major "functional areas." These are Incident Command, Operations, Planning, Logistics, and Finance/Administration. There is an optional functional area, Intelligence/Investigations, that can exist when an incident involves criminal activity. The five major functional areas are basically structured like this:

A useful mnemonic for remembering the five major functional areas is COPLAFs (as in “cop laughs,” an acronym for Command, Operations, Planning, Logistics, and Administration/Finance.) On a small incident, one or two individuals may be sufficient to carry out all of the functions.

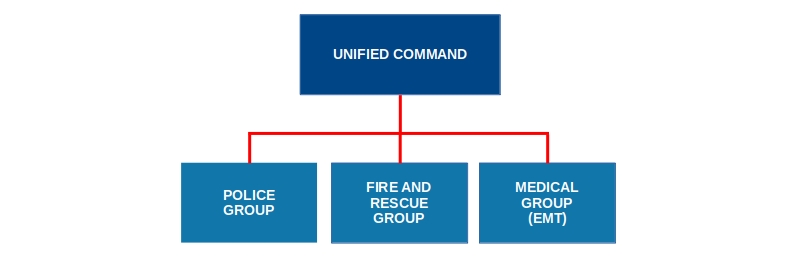

Regardless of size, every incident requires a leader. In the ICS, the leader is usually called the Incident Commander. Sometimes he or she is rhetorically called Incident Command or IC. Occasionally, the Incident Command position may be filled by multiple persons and designated as Unified Command. In any case, the command function is the first to be filled, is always filled, and remains filled for the duration of an incident.

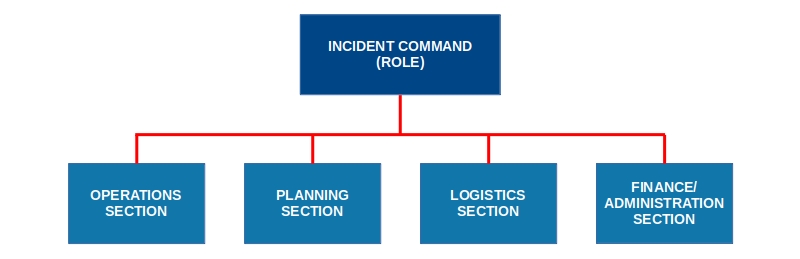

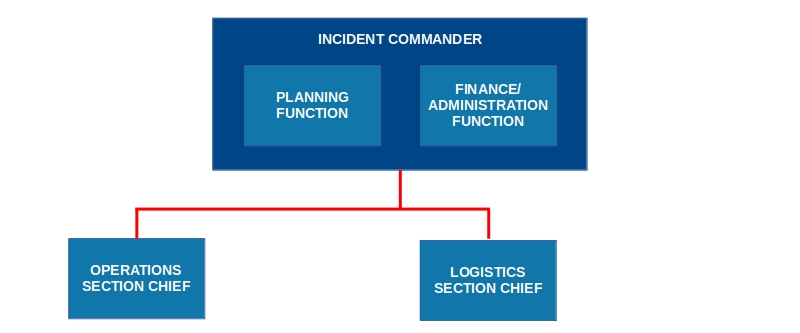

In a very small incident a single person might be able to perform the Incident Command function as well as all of the other functions. If an incident becomes large enough that a functional area requires its own leader, the functional area becomes a managerial section:

These sections are assigned leaders who are collectively called the General Staff and are individually called Chiefs. A mnemonic for the Incident Commander and the four Section Chiefs is 5 Cs (“five-cees”) for Commander, Chief, Chief, Chief, Chief, in Sections.

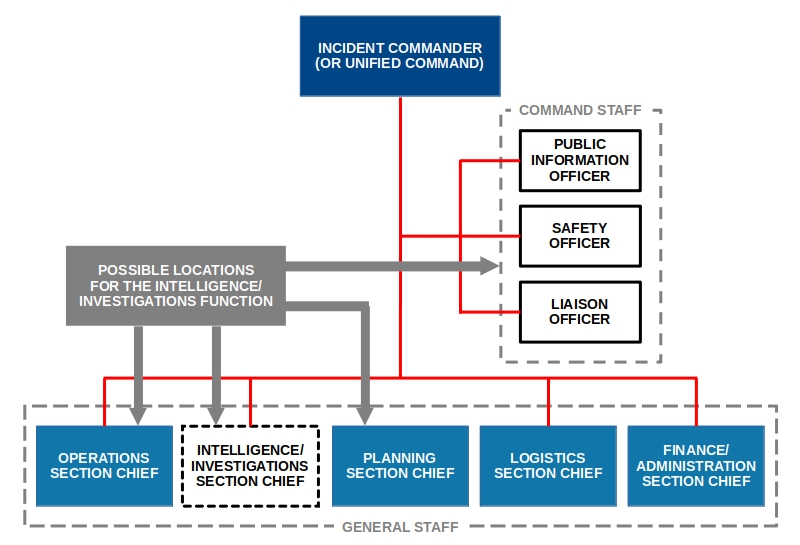

The Incident Commander might have three specifically-named assistants if the size of the incident requires them. These assistants are collectively called the Command Staff and individually called Officers. ICS lists three Command Staff positions: a Public Information Officer, a Safety Officer, and a Liaison Officer. A mnemonic for this is PIO-SOLO for Public Information Officer, Safety Officer, Liaison Officer.

Try not to confuse Function with Section, General Staff with Command Staff, and Chief with Officer. General Staff are leaders; Command Staff are assistants.

Do not to confuse a fire or police chief with an ICS section chief. The two positions might or might not be occupied by the same person. And do not confuse Command Staff officers with law enforcement officers.

When required, the Intelligence/ Investigations functional area and its personnel could be fitted into the Command Staff area, into other sections, or into its own section depending on the situation:

ICS specifies additional structures that may exist within the four functional areas. The number and arrangement of such structures varies according to the situation. For conceptual purposes, the ICS literature provides a diagram that is essentially reproduced here:

You might have noticed that the Command Staff in this image is diagramed slightly differently from the previous image. Do not get hung up on it. This is how it was done in the official literature, and the meaning is identical in both depictions.

At a medium sized incident, the functional areas might be small enough to assign a single leader to lead two areas. The Operations Section Chief could also be the Planning Chief for example. Alternatively, there might not be enough activity to create certain sections. An Incident Commander could create a Operations Section and a Logistics section and perform any Planning and Finance/Administration functions him or herself:

The Place of the EMT in ICS

There are two functional areas under which a new EMT would typically serve: Operations and Logistics. In practice, an EMT would almost always take instructions from his or her regular supervisor.

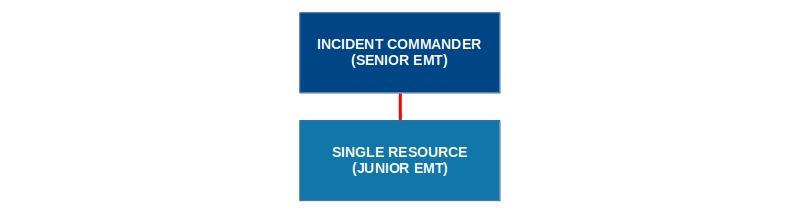

Imagine a basic life support ambulance staffed by two EMTs. The crew has been called to an incident where a person has slipped on ice and needs transportation to a hospital. Assuming there are no other emergency responders present, the senior EMT would take Incident Command and both EMTs would perform any of the required the four ICS functions together.

The primary function would be Operations, but with this size of an incident there would be no reason to consider the functions separately:

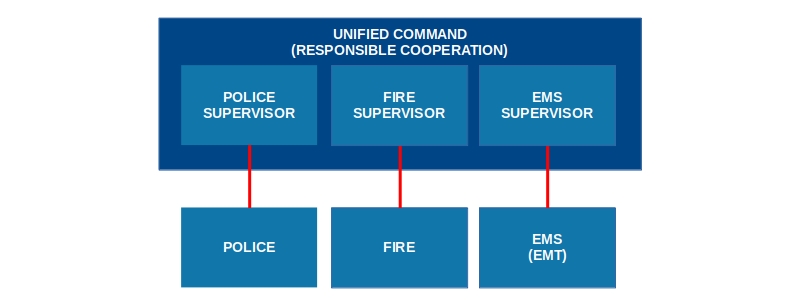

In a larger incident such as a motor vehicle collision with multiple patients, an EMT could serve in a medical group acting in an operational capacity under a unified command. According to FEMA standards, the organizational chart would look something like this:

A clearer depiction would look like this:

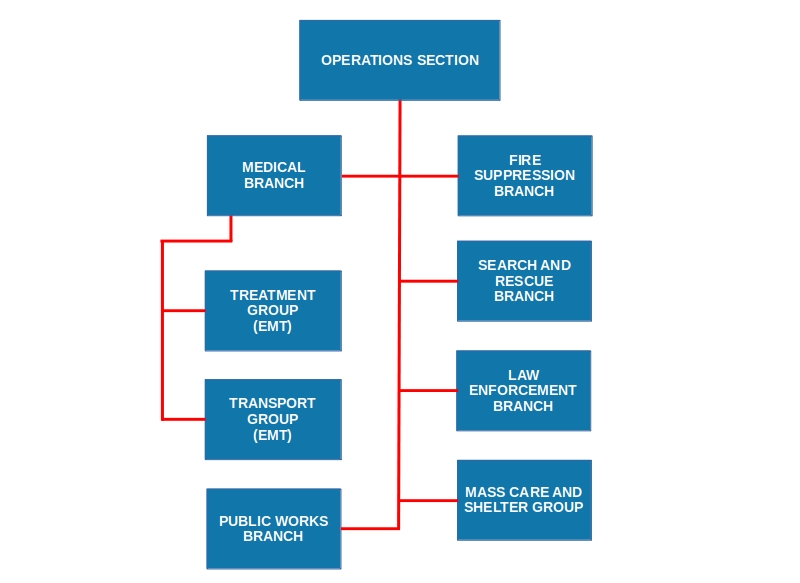

In a much larger incident such as a tornado or flood with multiple injuries, an EMT could be assigned to a medical, EMS, or health branch within the Operations Section. Within the branch he or she might be assigned to a treatment or transport group:

In very large incidents, emergency medical personnel could also be performing triage, medevac, or communication duties in other areas of ICS.

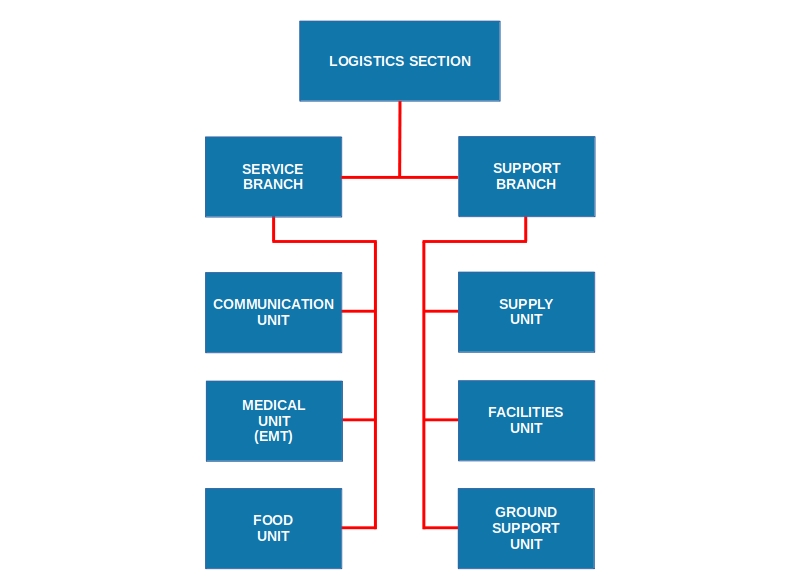

In a large incident with few or no injuries such as a prairie fire, an EMT could be assigned to the Logistics Section on standby, probably in a forward staging area, to provide treatment and rehab services to the firefighters and other responders:

In some incidents, such as a cyber attack, an EMR or EMT would not have any involvement in the resultant ICS structure. Finally, never, never forget that except while performing basic first aid while off duty, an EMR's or EMT's top medical supervisor is his or her medical director.

ICS Nuances

This is the level at which the system starts to get complicated, and I will share some general observations and thoughts.

Incident Commander is a misnomer since the Incident Commander does not actually command in most cases like a military officer but rather manages like a business leader.

One benefit of this business-leader model is that it encourages aid from others who would not be or who would not want to be seen as subordinates. For example, if a volunteer fire department chief is the Incident Commander at an incident that is linked to interstate crime, the FBI would get involved. There is not a FBI agent in the world who is going to take orders from a volley chief.

In addition to a three-person Command Staff, the Incident Commander may have one or more assistants called Deputies. A General Staff Chief may also have one or more assistants also called Deputies. This can be confusing. It is assumed that the title Deputy is followed by the corresponding superior's title, i.e. Deputy Incident Commander, Deputy Operations Chief, etc. A Deputy should be able to fill his or her superior's position.

The three Command Staff Officers, who are assistants to the Incident Commander, may also have assistants called Assistants (i.e. Assistant Public Information Officer, Assistant Safety Officer, Assistant Liaison Officer.)

A branch is an ICS organizational level having functional or geographical responsibility for major aspects of incident operations. Branches are established within a section when the span of control becomes excessive (approximately more than 5 subordinates for each 1 supervisor.)

A Unit is an unusual ICS component. It is supposed to appear only within the Planning, Logistics, and Finance/Administration Sections. I do not know the reason for this. I have seen SWAT Unit in the ICS literature, and anything with SWAT operators would likely be in the Operations Section. I suppose this is an editing oversight or a holdover from earlier days. Knowing that Unit means one and that there is one Section in which Unit does not fit might be a useful mnemonic.

A Task Force is a combination of mixed resources with common communications operating under the direct supervision of a Task Force Leader. Whereas, a Strike Team is a set number of resources of the same kind and type with common communications operating under the direct supervision of a Strike Team Leader. A way to help remember the difference between Task Force and Strike Team is with the mnemonic Strike-like.

A Group is a team "established to divide the incident "into functional areas of operation.

It is unclear to me at this time how a Task Force or Strike Team differs from a Group. I assume that it has something to do with the risk associated with the position, since Task Force and Strike Team are macho sounding whereas Group is not. In any case, I do not think the distinction is important for passing the basic tests.

Divisions are established to divide an incident into physical or geographical areas of operation such as floors of a building or sides of a city. Thinking about dividing a pie or pizza might help to remember this since the division of a pie or pizza results in physical objects.

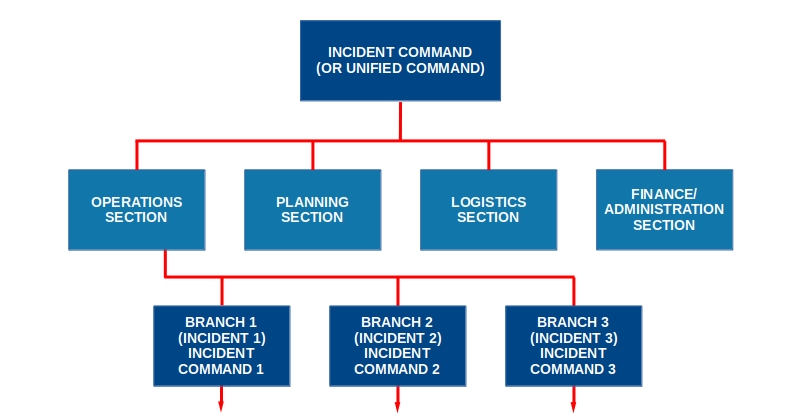

In a complex situation, the basic ICS structure can be propagated and managed in various ways. One way involves branches in the mother structure's operations sections becoming their own basic structures:

If a situation ever gets this bad, you might also see the command role identified as Area Command or Unified Area Command.

NIMS

ICS is a component of a parent component called Command and Control. Command and Control, itself, is a component of a parent system called the National Incident Management System (NIMS). This can be complicated and dull, so to explain it, we will will work outward from NIMS and then clarify with a large diagram.

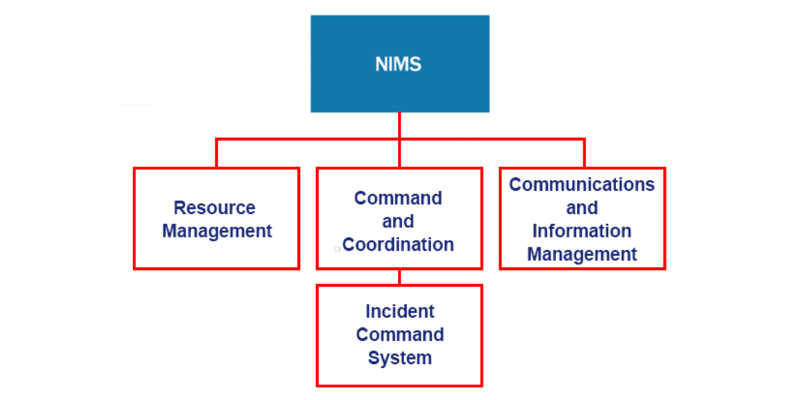

NIMS has three major components, whether these components are systems, sub-systems, or parts, or some type of hybrid depends on whom one asks. In any case, the three major components are (1) Resource Management, (2) Command and Coordination, and (3) Communications and Information Management:

NIMS also reportedly has minor components. Those cited in the literature are the principles of prevention, flexibility, standardization, and unity of effort. There might be even more NIMS components in some of the advanced literature, but these would not matter for basic certification.

1. Resource Management

The first major NIMS component is Resource Management. Resource has a broad meaning and includes whatever can be used to deal with an incident. It could be a map, a dog, a person, a crew, a hammer, a backhoe, a helicopter, a base, a fire department, the US Army, etc.

The Resource Management component is defined in the government literature as “systems [Notice the plural.] for identifying available resources at all jurisdictional levels to enable timely, efficient, and unimpeded access to resources needed to prepare for, respond to, or recover from an incident.” This basically means knowing what resources are needed, what are in stock, where they are located, what are available, what are being used used, and where to beg, buy, borrow, or rent more.

The Resource Management Component has three components that may be described as:

- The four key activities of NIMS Resource Management Preparedness

- Resource management during an incident

- Mutual Aid

The four key activities are in fact nine activities that are arranged in four categories:

- Identifying and typing resources.

- Qualifying, certifying, and credentialing personnel.

- Planning for resources.

- Acquiring, storing, and inventorying resources.

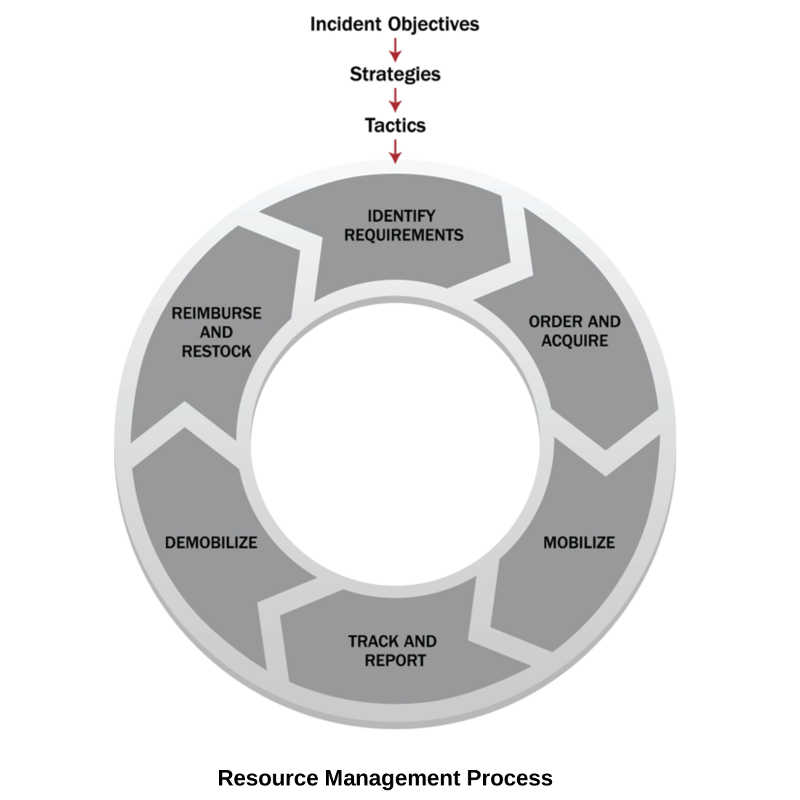

Resource management during an incident is summarized by the following diagram:

The Mutual Aid component is very briefly touched upon. This is probably for touchy political and legal reason.

2. Command and Coordination

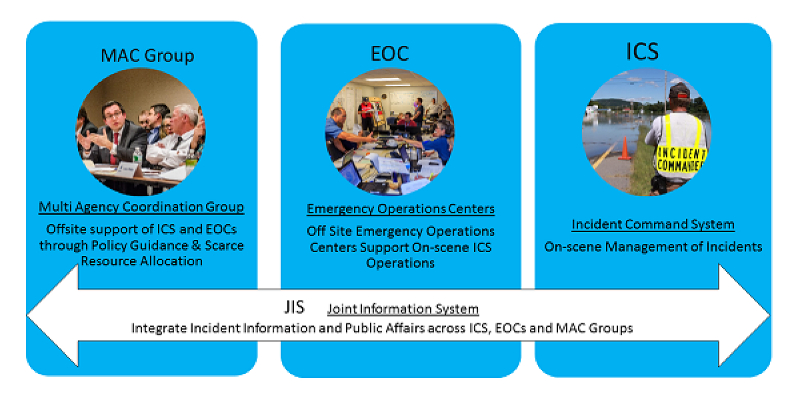

The second major NIMS component is Command and Coordination which is defined in the ICS-700 literature in various ways. As nearly as I can tell, it is a system composed of another system, the Incident Command System (ICS), and two other major components, an Emergency Operations Center (EOC) and a Multi-agency Coordination (MAC) Group. There could be more than one of these components in a very large incident. These three (or more) major components are connected together by yet another system, the Joint Information System (JIS), which has at least two supporting components, a Public Information Officer (PIO) and a Joint Information Center (JIC).

It is assumed (but unclear from the basic literature) that the Public Information Officer is a similar position as the one in ICS, and it would be filled in lieu of the ICS position in the case of a complex or large incident. In any case, FEMA depicts the relationship like this:

NIMS bases the Command and Coordination component on fourteen NIMS Management Characteristics. The NIMS part seems to be somewhat misleading; I have only seen the 14 Characteristics mentioned in relation to the Command and Coordination System. Nevertheless, they are common sense principles that may be applied to other parts of your life. They appear frequently in the ICS literature, so I will repeat them here numbered:

- Common Terminology

- Modular Organization

- Management by Objectives

- Incident Action Planning

- Manageable Span of Control

- Incident Facilities and Locations

- Comprehensive Resource Management

- Integrated Communications

- Establishment and Transfer of Command

- Unified Command

- Chain of Command and Unity of Command

- Accountability

- Dispatch/Deployment

- Information and Intelligence Management

The fourteen principles themselves are often built around sub-principles framed as "qualities." For example: Integrated Communications is stated as necessary to maintain connectivity, achieve situational awareness, and facilitate information sharing. There are a few nuances in these sub-principles that merit commentary.

The Manageable Span of Control principle states that the optimal span of control is one supervisor to five subordinates. This conflicts with a typical Incident Commander span of control which could be 8 or more individuals: 3 Command Staff officers and 5 General Staff Chiefs (including an Intelligence/Investigations Chief) as well as any Deputies.

The Unified Command principle also conflicts with ICS. In an emergency or significant incident, it is important to have a single person in charge. This cannot always occur for various reasons. One notable reason (and one that is not surprisingly omitted from the literature) is that political posturing might lead to drama between leaders of separate jurisdictions over who gets blame for a disaster or who gets credit for a successful outcome. NIMS skirts the issue with the concept of Unified Command. One way to think of Unified Command is to compare it to a 3-general junta that has taken power in a lesser-developed-nation after a military coup.

One principle of the Dispatch/Deployment characteristic is to wait until formally activated. This makes sense when the chaotic origin of ICS is considered. During a major forest fire, one of the last situations a fire chief would want to see is a traffic jam of self-dispatchers along a narrow woodland road that prevents the movement of equipment and could trap everybody in an inferno. However, there are many incidents in which a wait-until-called response would be out-of-line at the least and dishonorable at the worst. For example, if you were to see a child bleeding-out on the side of a road, you would not wait for someone to tell you to help.

If you have read that you should wait to be activated and are questioned about it on a test, answer according to what you read.

3. Communications and Information Management

The third major component of NIMS is Communications and Information Management, which is basically a collection of principles and policies for dealing with and controlling communication and information. It may be summarized as four sub-components:

- Four key principles of communications and information management.

- Communications management practices and considerations.

- Incident information use.

- The three concepts related to Communications Standards and Formats.

In keeping within officialese standards, the four key principles of communications and information management are in fact seven principles arranged in four categories:

- Interoperability.

- Reliability, Scalability, and Portability.

- Resilience and Redundancy.

- Security.

And the three concepts related to Communications Standards and Formats are in fact seven concepts arranged in three categories:

- Common Terminology, Plain Language, and Compatibility.

- Technology Use and Procedures.

- Information Security/Operational Security.

Communications and information management is obviously not exclusive to the Communications and Information Management component. I suppose the item merits its major component status because without information and communication, NIMS is useless.

If I recall correctly none of these concepts was on the test, or if one was, it was asked in such a simple, common sense way that any EMT could correctly answer such as: Is security a principle of communications and information management?

The National Preparedness System

NIMS is a component of a larger system. According to FEMA, NIMS is "built upon" to create one of the 5 frameworks that are integrated into the six components of the National Preparedness System. You will likely never need to know this as an EMT. For the record, the National Preparedness System is depicted in FEMA literature like this:

Thus, ICS is a system within the Command and Coordination component of the National Incident Management System, which is a system within the National Preparedness System, which is a system within the Federal Emergency Management Administration system, which is a system within the Department of Homeland Security, and so forth.

The National Preparedness Goal

The National Preparedness System is based on the National Preparedness Goal, which is a Department of Homeland Security mission statement. The only reason this is mentioned is that the National Preparedness Goal references the "whole community," and "whole community" appears frequently in the literature and is a likely test subject.

For ICS, the "whole community" means that non-emergency responders should be involved in incident management. Examples are the help by a child to translate for an EMT, the help of citizen volunteers to assist with search and rescue after a hurricane, and the help of churches to provide emergency food and shelter.

The Big Picture

A simplified system hierarchy could be depicted something like this (Notice the mix of tangible and intangible components.):

It should be obvious that there are countless other components to this hierarchy that are impossible to depict. There are also numerous variations, some more varied than the federal government recommends.

If you ever work as an ER tech, you might need to know about the Hospital Incident Command System, which seems to be in widespread use in California and has a structure similar to ICS.

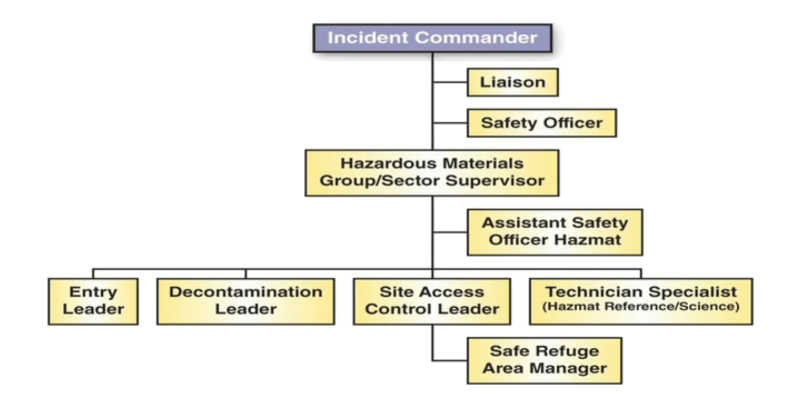

Some school districts, businesses, and local jurisdictions also seem to have their own systems. For example, the Pierce County, Washington, Hazardous Incident Team recently was and probably still is using this command structure:

You will need to know the Canadian and Australian incident management systems if you ever work in those wonderful lands. Both systems are similar to ours.

ICS as a Way of Life

The elegance of ICS comes from its adaptability to all sizes and types of incidents, including very small ones. Although not often thought of in this way, an ICS-structured response can apply to acts as small as cutting your grass, picking up debris, helping a neighbor, or planning a party.

For example, imagine that the grass around your home is getting tall. You realize that it would impede firefighter access in the event of a home fire so you cut it. You have just applied the NIMS first mission area of prevention.

Imagine you are walking on a sidewalk and you notice a board in the street with a nail sticking up that would likely cause a flat or blowout if a car or motorcycle were to drive over it. You, being a good citizen and after assuring scene safety, move it from the street. You have again applied the mission of prevention. And in this case and the previous one you have been the Incident Commander who fulfilled an Operations function.

Imagine you are in a restaurant and someone clutches his chest and collapses. You take command. The first thing you do is to assure scene safety, thus fulfilling your primary responsibility as the Incident Commander. You check the patient and tell someone to call 911. That person is essentially (but not actually) your Liaison Officer. You tell another person to get an AED. That person is essentially your Logistics Chief. You treat the patient, fulfilling an Operations function. When an ambulance arrives you transfer command to a paramedic.

Imagine you decide to throw a surprise 50th anniversary party for your grandparents. You take the Incident Command role. You give one sister the Operations Chief position, she agrees to use her house, host the event, and keep her son from drinking too much. You give another sister the Planning Chief position, she determines who will attend and where everyone will sit. You give a cousin the Logistics Chief position, he will bring the table and chairs, and pick up the cake. Your parents, aunts, and uncles agree to share the cost, so you enlist your father for the Finance/Administration role to keep track of expenses.

My Experience with the Tests

During my licensing process (in Texas) I was told that I needed three certifications: ICS-100, ICS-200, and ICS-700, and I could complete these online through FEMA's Emergency Management Institute website.

To make a long story short, there are no FEMA classes with those specific names, but there are classes for "IS-100.c Introduction to Incident Command System, ICS-100," "IS-200.b ICS for Single Resources and Initial Action Incident, ICS-200" and "IS-700.b An Introduction to the National Incident Management System." These were the classes I took. The "IS" apparently stands for "Independent Study." I imagine that "b" or "c" is for a specific version and that the "ICS-100" and "ICS-200" are holdovers from an earlier and simpler time. Note that three classes focus on two different systems, ICS and NIMS.

The tests were much easier than I thought they would be. I studied harder than I needed to for the IS-100 certificate. But this helped later because much of what is required to pass the IS-100 test is required to pass the other tests. I passed all the tests on the first attempts. I also scored higher than I needed to pass, but if I recall correctly, I did not achieve perfect scores.

I had to ask for a re-issue of my certificate for IS-200 because of a mis-spelling of my name, (which was promptly corrected). My current certificate for IS-700 has a printing error of “Sys” for “System.” I suppose there was no enough space for the entire word. The class names on my physical certificates have additional zeros (i.e. "IS-00100.c.") None of the nomenclature or printing issues prevented me from getting licensed, but they are the type of distractions that a detail-oriented person could find annoying.

Contrary to first impressions, ICS is an excellent management system. The way it is framed and described by FEMA does not do it justice. My advice to anyone trying to learn ICS would be to not get hung up on the officialese, to take advantage of mnemonics, to slog through the literature, to look at the big picture, and to play around with my apps.

A Final Thought

At one time, FEMA was paying senior managers very well (up to $183,500 per year plus benefits,) and California had similar positions that were well over 6 figures. This is something to keep in mind as you work your way through FEMA literature and if you think that someday you might want to help others in a different and more lucrative capacity than as an EMR or EMT.