The American Civil War "Paramedic"

And his Battlefield Brothers in Action

This article will review several, lower level, medical textbooks of the time leading up to and including the American Civil War. The assumption is that they describe the first aid knowledge, treatment options, and skills of the era's equivalent to the modern paramedic, AEMT, EMT, and EMR. Such old-timers would typically be assistant surgeons, surgeon assistants, ambulance attendants, and ambulance drivers. These positions and their roles could have varied according to the time in the war and the units involved.

The Medical Remembrancer, or, Book of Emergencies:

in which are Concisely Pointed out the Immediate Remedies to be Adopted in the First Moments of Danger from Poisoning, Apoplexy, Burns & other Accidents : with the Tests for the Principal Poisons & other Useful Information.

This 120-page book with its old-style, lengthy title is attributed to a British surgeon and apothecary, was “Revised and Improved by an American Physician,” and has a publication date of 1845. That it was first published in London, England, lends weight to the idea that the United States was a backwater of medicine. That the “American Physician” is not named suggests that individual was not a physician or that he did not want his colleagues to know that he was spreading the secrets of their trade.

The first chapter concerns poisons and their supposed remedies. Although painfully dull, three areas are noteworthy. The first is a method of artificial respiration: “It is easily accomplished by making strong pressure with both hands on the anterior surface of the chest, the diaphragm being at the same time pushed upwards by an assistant, while inspiration is effected by the mere removal of the pressure, and consequent resiliency of the ribs.” The second is a method of what is now known as defibrillation: “Another powerful means of restoring sensibility and respiration is electricity, or what is better, electro-galvanism; the best method of allying this, is to place one wire at the nape of the neck and the other at the pit of the stomach, so as to excite the diaphragm.” The third is the use of cannabis as an antidote to strychnia (strychnine?) poisoning: “It acts as a sedative and produces the most complete relaxation of the muscular system without endangering the patient's life, even in large doses, it merits a trial whenever it can be procured in time.”

The second chapter deals with accidents and is generally an interesting read. Much of it deals with bloodletting, which was commonly called bleeding. For the uninitiated, blloodletting is a formerly widespread practice of attempting to prevent or cure illness by removing some of (and often a fatal amount of) a patient's blood. The author recommends it as a treatment for apoplexy, or stroke; drowning; rabies; burned throat; brain injury; bruising; epilepsy; croup; drunkenness; nosebleeds; sprains; and puncture wounds. The 1845 first responder was also instructed to give a stroke victim an emetic and to pump wine into a drowning victim's stomach.

The third chapter contains instructions for “minor operations:” bleeding; cupping, or applying suction to the skin using glass cups; electric shocks; issues, or creating deliberate skin blisters; laryngotomies, or cricothyrotomies; tracheotomies; oesophagotomies, or surgically removing food lodged in an esophagus; stomach pumping; and vaccinating. All of this is described in 17 paragraphs.

The forth and final chapter describes how to detect specific poisons. The average modern reader would find it deathly dull, but a pharmacist might find it interesting.

Accidents and Emergencies:

A Guide Containing Directions for Treatment in Bleeding, Cuts, Stabs, Bruises, Sprains, Ruptures, Broken Bones, Dislocations, Railway and Steamboat Accidents, Burns and Scalds, Explosions, Bites of Mad Dogs, Inflammations, Cholera, Diarrhea, Injured Eyes, Choking, Poisons, Fits, Sun Stroke, Lightning, Drowning, etc., etc.

Co-written by a British Surgeon and a Dr. Trall, this 43-page book was published in New York in 1850. It is noteworthy for several reasons, the most obvious of which is that it does not prescribe bloodletting.

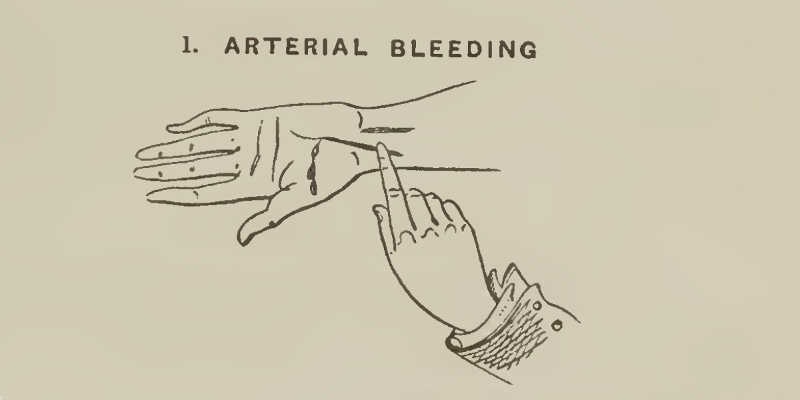

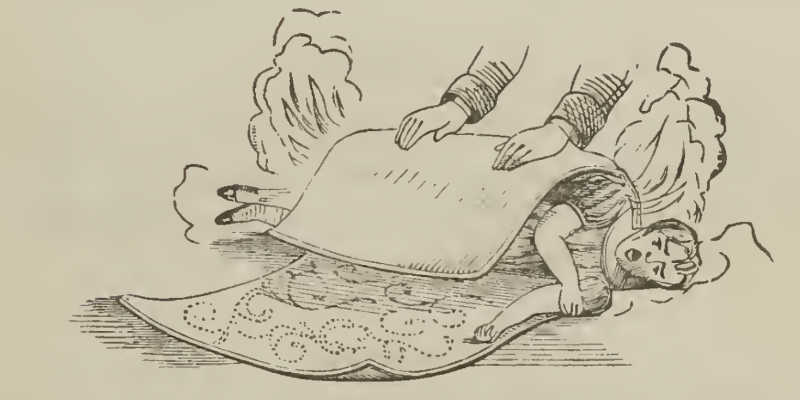

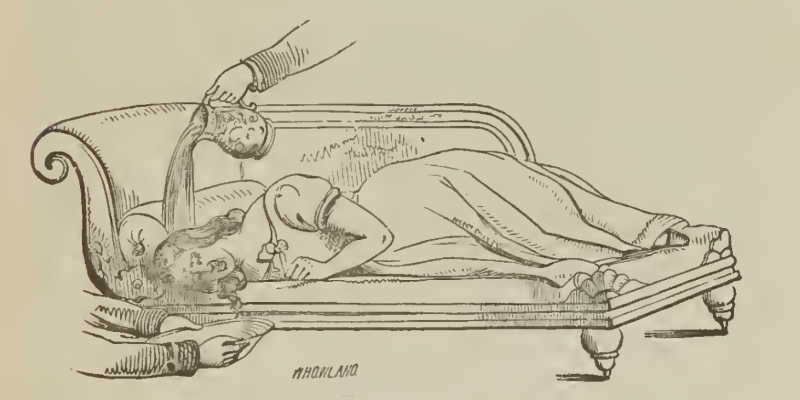

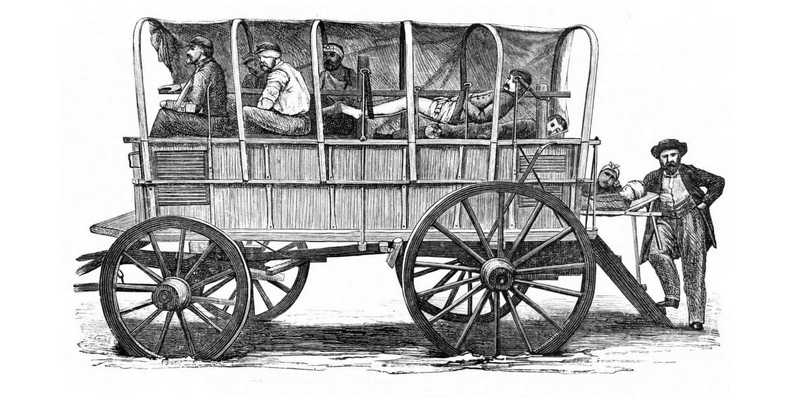

Accidents and Emergencies is relatively well written for the times. The authors recommend cleaning incisions “from dirt or other extraneous matter” and providing rest and ice to treat sprains. Treatments are cross-referenced. Numerous engravings illustrate skills such as controlling bleeding with direct pressure, moving a patient, creating a splint, extinguishing a clothing fire, removing a foreign body from an eye, positioning a patient, performing rescue breathing, and checking for a radial pulse. The appendix, which promotes “the water cure,” would tend to encourage health through cleanliness.

One the other hand, the book still has a medieval aspect. No theory is given to support “the water cure.” The treatment given for frostbite is to rub the afflicted area with snow; for choking, it is to thrust one's fingers as far down the patient's throat as possible. A piece of wood is recommended to be placed in the mouth of a patient having an epileptic attack. Pouring cold water on the head of a patient is the recommended treatment for “hysterics.”

Flatulence is given as a cause of “fainting fits;” and the final pages contain advertisements for phrenology books, which promote the idea that personality traits can be determined by bumps on a person's head.

Brief Directions for the Treatment of Accidents, and the Course to be Pursued in Cases of Poison, the Bite of Venomous Insects, and Directions for Performing Simple Surgical Operations, to which are added a few Simple Medical Recipes, and Instruction for Sick Cookery.

The first point of interest with this book is that its author is basically anonymous. He claims to be a physician with the initials H.P.R. The date of publication is 1852. The city of publication is Washington, D.C. The length is 82 pages. There are no illustrations.

Another point of interest —and one that might be a factor in the first —is that many parts are very similar to The Medical Remembrancer. The similarity is so close that it suggests that this book is simply a derivative work compiled from The Medical Remembrancer and similar writings. The final chapter contains recipes for such dishes as chicken broth, eel broth, veal broth, and bread soup, some of the “Simple Medical Recipes” mentioned in the title.

The Homoeopathic Surgical Adviser and Traveler's Companion; Containing also the Treatment in Cases of Poisoning.

This 84-page book was published in Philadelphia, in 1859, with the stated intention “to give clear and easily understood instructions for the treatment of accidents, when no medical attendance can be procured….”

Homoeopathic (modern spelling: homeopathic) is an adjective describing a medical belief that an illness or injury can be treated with small amounts of the substances that produces the symptoms of the illness or injury. Although some could try to argue that there are homeopathic cures (i.e. defibrillation), underlying theories are different, and homeopathy has been discredited.

Some examples of homeopathy in this book can be seen in the treatment for first degree burns: “dry heat, applied by holding the injured part as closely as possible to the fire;” and in the treatment for severe frostbite: “If you have snow, cover him with it, face and all, leaving only the mouth and nostrils free….” Some of the recommended medicines also appear to be based on homeopathic theory. For example, wine or brandy are recommended for seasickness.

Nevertheless, every treatment in this book is not homeopathic, and a few appear to be valid ones. For example, pressure is the recommended treatment for bleeding. It is noteworthy that bloodletting is not mentioned. Cupping is mentioned only for snakebites. An artificial respiration technique is described that involves rolling a patient back and forth between prone and supine positions.

A Manual of Minor Surgery

Attributed to John H. Packard, M.D., containing 145 illustrations, and adopted by the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, one can assume that this 1863, 300-page manual was on the cutting edge of Civil War medicine. (Some of its illustrations are not safe for work.) Many ideas in it are attention grabbing.

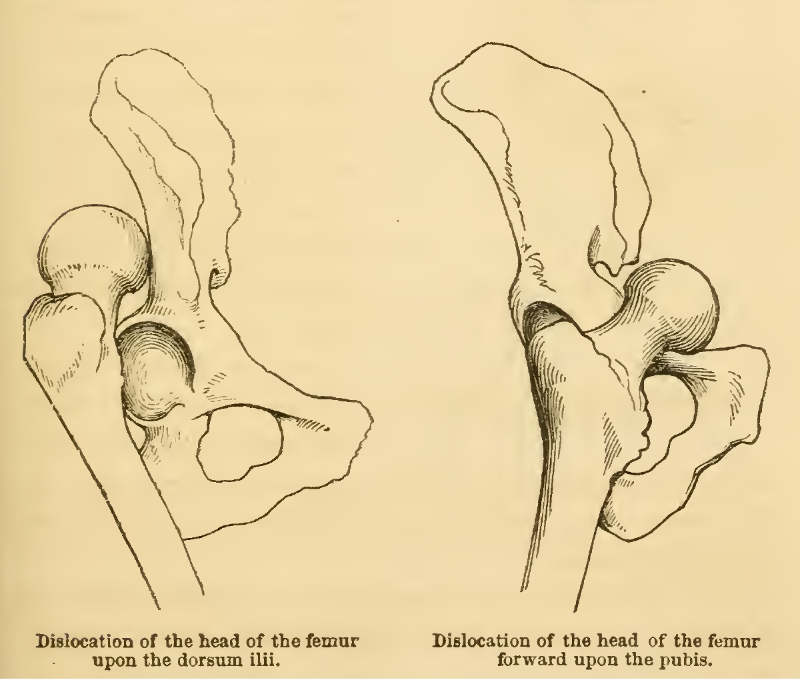

One of these concerns bleeding. What is unusual is that some thought has clearly been put to the subject, which is referred to as “surgical distension.” The operative word in this term is “distension,” meaning that bleeding could serve as a relaxant or sedative. Bleeding a patient into unconsciousness in order to be operated on may seem ludicrous to us, but could have been useful in a time when some would have chosen suicide over going under the knife while alert to person, place, time, and pain. Likewise, bleeding a patient into unconsciousness in order to relax him or her enough to reduce a dislocated bone could have been a logical treatment if anesthetics were not available.

Another idea of interest is Dr. Packard's concept of minor operations, which he writes, “are, as a general rule, simple and free from danger.” These include the opening of abscesses; the laying open of sinuses; the use of ligatures to treat hemorrhoids; correcting harelips on children; vaccinating, including the manufacture of the vaccine using saliva; cauterizing; and several operations on male genitals. Reducing compound dislocations is noted as being outside of the scope of the text, but the recommendation for treating a compound fracture that cannot be reduced is to saw off the projecting bone.

The most salient part of this book is the idea that Dr. Packard was very close to but not quite at the point of recognizing the importance of pathogens. There are numerous references to cleanliness, including an entire chapter about disinfectants. Dr. Packard notes that infections are more common in crowded quarters and that: “We cannot but attribute it to atmospheric influence, whether we suppose organic particles, or fomites floating in the air, or adopt a more purely chemical theory, such as that of catalysis.” There is, however, no explicit mention of body substance isolation.

Antiquated texts such as these are still valuable. They can be entertaining from both a historical perspective and a horror-show perspective, and they can provide gist for lively conversations. But they can also help in calibrating emotions. For example, witnessing an autopsy might be less disturbing if one knew that in an earlier day the postmortem exam might have been performed in a private dwelling and surgery on a kitchen table.

In terms of medical history, the crude medical care of the Civil War is not far removed from the present day. Understanding this, can help one be more tactful when steering members of lesser developed cultures (such as some immigrants) away from traditional and harmful treatments (such as rubbing snow on a frostbitten body part). Moreover, understanding the profession's history can promote confidence in the out-of-hospital emergency care provider and can lead to a greater understanding of medicine's trajectory and of our transition into the future.